The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) is a 69-item self-report inventory for the assessment of self-attitudinal aspects of the body-image construct. Body image is conceived as one’s attitudinal dispositions toward the physical self (Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990). Of the available measures of attitudinal body image, the Multidimensional Body Self- Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) (Cash, 2000) is the most widely used (Grogan, 2008;Duncan & Nevill, 2010).

Multidimensional Body Self Relations Questionnaire User Manual Download

Multidimensional Body Self Relations Questionnaire User Manual 2016

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

1

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL BODY-SELF RELATIONS QUESTIONNAIRE THOMAS F. CASH, PH.D Professor of Psychology Old Dominion University Norfolk, VA 23529-0267 Office phone: (757) 683-4439 University E-mail: [email protected] Personal E-mail: [email protected]

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) is a 69-item self-report inventory for the assessment of self-attitudinal aspects of the body-image construct. Body image is conceived as one’s attitudinal dispositions toward the physical self (Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990). As attitudes, these dispositions include evaluative, cognitive, and behavioral components. Moreover, the physical self encompasses not only one’s physical appearance but also the body’s competence or “fitness” and its biological integrity or “health/illness.” An initial version of this instrument in 1983 contained 294 items and was termed the BSRQ. Subsequent versions iteratively eliminated or replaced items on the basis of rational/conceptual and psychometric criteria. In 1985, Cash, Winstead, and Janda used the instrument in a national body-image survey. From over 30,000 respondents, approximately 2,000 were randomly sampled, stratified on the basis of the sex X age distribution in the U.S. population. In addition to the original publication of survey results (see Cash et al., 1986), numerous publications have developed from analysis of this database and from research with other diverse samples (see appended references). A cross-validated principal-components analysis of the original database (Brown, Cash, & Mikulka, 1990) supports the conceptual components of the instrument. The MBSRQ’s Factor Subscales reflect two dispositional dimensions—“Evaluation” and cognitive-behavioral “Orientation” –vis-à-vis each of the three somatic domains of “Appearance,” Fitness,” and “Health/Illness.” A minor exception was an emergence of separate Health and Illness Orientation factors. In addition to its seven Factor Subscales, the MBSRQ has three special multiitem subscales: (1) The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS) approaches body-image evaluation as dissatisfaction-satisfaction with body areas and attributes (similar to earlier inventories, such as Secord and Jourard’s Body Cathexis Scale, Bohrnstedt’s Body Parts Satisfaction Scale, and Franzoi’s Body Esteem Scale). (2) The Overweight Preoccupation Scale assesses fat anxiety, weight vigilance, dieting, and eating restraint. (3) The Self-Classified Weight Scale assesses self-appraisals of weight from “very underweight” to “very overweight.” The MBSRQ is intended for use with adults and adolescents (15 years or older). The instrument is not appropriate for children. If researchers administer the full 69-item

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

2

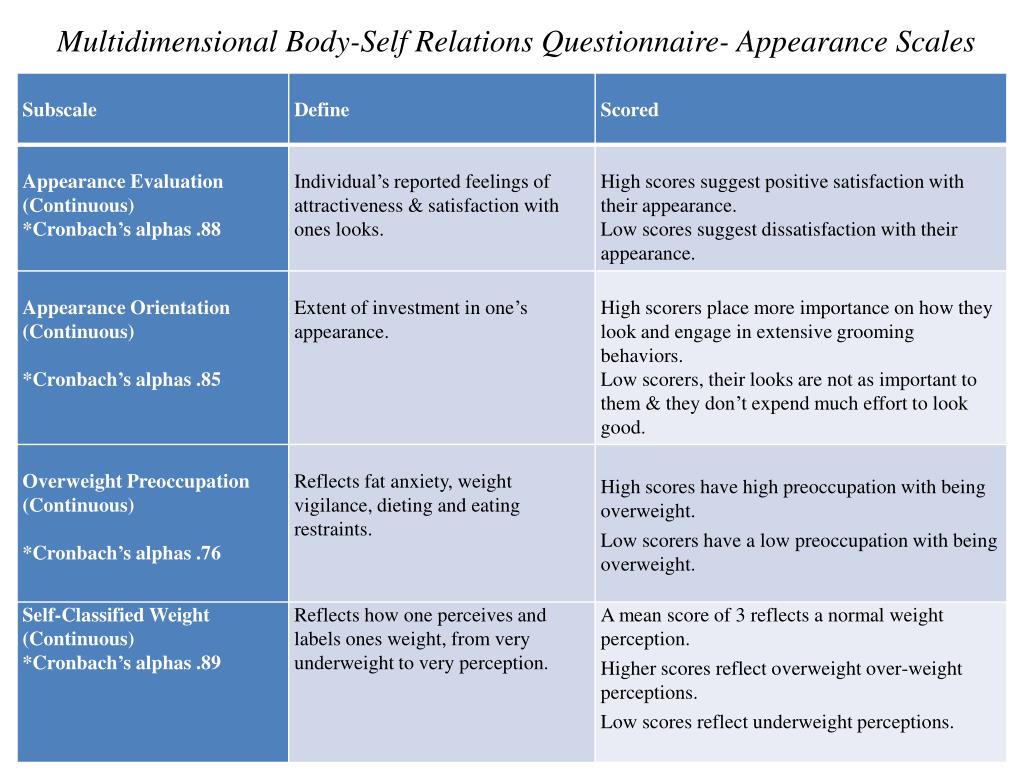

MBSRQ but wish to reduce the number of derived scores, the Fitness Evaluation and Health Evaluation scales may be combined (i.e., averaged) to calculate a Fitness/Health Evaluation measure. Similarly, an average of the Fitness Orientation and Health Orientation scores may be computed to construct a Fitness/Health Orientation measure. Many body-image researchers are principally interested in the appearance-related subscales of the MBSRQ and wish to administer a shorter questionnaire that excludes the fitness and health items. Accordingly, they may elect to use the 34-item MBSRQAS (MBSRQ-Appearance Scales) version of the instrument. The MBSRQ-AS includes the following subscales: Appearance Evaluation, Appearance Orientation, Overweight Preoccupation, Self-Classified Weight, and the BASS. Unique in its multidimensional assessment, the MBSRQ has been used extensively and successfully in body-image research. Investigations range from basic psychometric studies to applied and clinical research, involving both correlational and experimental methodologies. The MBSRQ has been employed in national survey research, studies of “normal” college students, investigations of obesity, eating disturbance, androgenetic alopecia, facial acne, and physical exercise, and outcome studies of body-image therapy. The MBSRQ manual provides interpretive information about its subscales (PAGE 3), scoring formulae (PAGES 4-5), gender-specific norms (PAGE 6), and reliability data (PAGE 7). All subscales possess acceptable internal consistency and stability. References are also given for the author’s published research pertinent to the validity and clinical utility of the MBSRQ (PAGES 8-10). These cited sources confirm the MBSRQ’s strong convergent, discriminant, and construct validities. Terms and Conditions of Use of the MBSRQ The MBSRQ and its manual are available for a nominal fee from Dr. Cash’s web site. By providing certain identifying information and agreeing to honor payment of the fee to him, requestors can print (but not download) one copy of the MBSRQ and MBSRQ-AS, as well as the manual. Requestors are permitted limited duplication of the materials for research or clinical purposes. Conditions of use are as follows: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Period of use cannot exceed two years. Duplicated copies exceeding 500 require the author’s written permission. Distribution for use by others is prohibited. Re-typing or modification of the MBSRQ items is prohibited. Any commercial use of the materials, other than use in research or clinical practice, is prohibited. (6) Any document (i.e., technical report, thesis, dissertation, or published article) resulting from use of the MBSRQ will include its proper citation.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

3

THE MBSRQ SUBSCALES: INTERPRETATIONS The Factor Subscales: APPEARANCE EVALUATION: Feelings of physical attractiveness or unattractiveness; satisfaction or dissatisfaction with one's looks. High scorers feel mostly positive and satisfied with their appearance; low scorers have a general unhappiness with their physical appearance. APPEARANCE ORIENTATION: Extent of investment in one's appearance. High scorers place more importance on how they look, pay attention to their appearance, and engage in extensive grooming behaviors. Low scorers are apathetic about their appearance; their looks are not especially important and they do not expend much effort to 'look good'. FITNESS EVALUATION: Feelings of being physically fit or unfit. High scorers regard themselves as physically fit, 'in shape', or athletically active and competent. Low scorers feel physically unfit, 'out of shape', or athletically unskilled. High scorers value fitness and are actively involved in activities to enhance or maintain their fitness. Low scorers do not value physical fitness and do not regularly incorporate exercise activities into their lifestyle. FITNESS ORIENTATION: Extent of investment in being physically fit or athletically competent. High scorers value fitness and are actively involved in activities to enhance or maintain their fitness. Low scorers do not value physical fitness and do not regularly incorporate exercise activities into their lifestyle. HEALTH EVALUATION: Feelings of physical health and/or the freedom from physical illness. High scorers feel their bodies are in good health. Low scorers feel unhealthy and experience bodily symptoms of illness or vulnerability to illness. HEALTH ORIENTATION: Extent of investment in a physically healthy lifestyle. High scorers are 'health conscious' and try to lead a healthy lifestyle. Low scorers are more apathetic about their health. ILLNESS ORIENTATION: Extent of reactivity to being or becoming ill. High scorers are alert to personal symptoms of physical illness and are apt to seek medical attention. Low scorers are not especially alert or reactive the physical symptoms of illness. Additional MBSRQ Subscales: BODY AREAS SATISFACTION SCALE: Similar to the Appearance Evaluation subscale, except that the BASS taps satisfaction with discrete aspects of one's appearance. High composite scorers are generally content with most areas of their body. Low scorers are unhappy with the size or appearance of several areas. OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION: This scale assesses a construct reflecting fat anxiety, weight vigilance, dieting, and eating restraint. SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT: This scale reflects how one perceives and labels one's weight, from very underweight to very overweight.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

4

ITEM NUMERS FOR EACH MBSRQ SUBSCALE (*REVERSE-SCORED ITEMS) APPEARANCE EVALUATION

5

11

21

30

39

42*

48*

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

1

2

12

13

22

23*

31

32*

40*

41

49*

50

FITNESS EVALUATION

24

33*

51

FITNESS ORIENTATION

3

4

6*

14

15*

16*

25*

26

34*

35

43*

44

53

HEALTH EVALUATION

7

17*

27

36*

45*

54

HEALTH ORIENTATION

8

9

18

19

28*

29

38*

52

ILLNESS ORIENTATION

37*

46

47*

55

56

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION

10

20

57

58

SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

59

60

MBSRQ subscale scores are the means of the constituent items after reversing contraindicative items (i.e., 1 = 5, 2 = 4, 4 = 2, 5 = 1). Alternatively, the formulae below may be used, which reverse-score items by subtracting them and adding a constant (i.e., any reversed item is scored as 6 minus the response value). Items are denoted as B1 to B69. COMPUTE APPEVAL = (B5+B11+B21+B30+B39-B42-B48+12)/7. COMPUTE APPOR = (B1+B2+B12+B13+B22+B31+B41+B50-B23-B32-B40-B49+24)/12. COMPUTE FITEVAL = (B24+B51-B33+6)/3. COMPUTE FITOR = (B3+B4 +B14+B26+B35+B44+B53-B6-B15-B16-B25-B34-B43+36)/13. COMPUTE HLTHEVAL = (B7+B27+B54-B17-B36-B45+18)/6. COMPUTE HLTHOR = (B8+B9+B18+B19+B29+B52-B28-B38+12)/8. COMPUTE ILLOR = (B46+B55+B56-B37-B47+12)/5. COMPUTE BASS = (B61+B62+B63+B64+B65+B66+B67+B68+B69)/9. COMPUTE OWPREOC = (B10+B20+B57+B58)/4. COMPUTE WTCLASS = (B59+B60)/2.

69

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

5

ITEM NUMERS FOR SUBSCALES OF THE MBSRQ-AS (*REVERSE-SCORED ITEMS) APPEARANCE EVALUATION

3

5

9

12

15

18*

19*

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

1

2

6

7

10

11*

13

14*

16*

17

20*

21

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

4

8

22

23

24

25

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

33

MBSRQ-AS subscale scores are the means of the constituent items after reversing contra-indicative items (i.e., 1 = 5, 2 = 4, 4 = 2, 5 = 1). Alternatively, the formulae below may be used, which reverse-score items by subtracting them and adding a constant (i.e., any reversed item is scored as 6 minus the response value). Items are denoted as B1 to B34. COMPUTE APPEVAL = (B3+B5+B9+B12+B15-B18-B19+12)/7. COMPUTE APPOR = (B1+B2+B6+B7+B10+B13+B17+B21-B11-B14-B16-B20+24)/12. COMPUTE BASS = (B26+B27+B28+B29+B30+B31+B32+B33+B34)/9. COMPUTE OWPREOC = (B4+B8+B22+B23)/4. COMPUTE WTCLASS = (B24+B25)/2.

34

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

6

ADULT NORMS FOR THE MBSRQ SUBSCALES

MALES

FEMALES

MBSRQ SUBSCALES MEAN SD

MEAN SD

APPEARANCE EVALUATION

3.49

.83

3.36

.87

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

3.60

.68

3.91

.60

FITNESS EVALUATION

3.72

.91

3.48

.97

FITNESS ORIENTATION

3.41

.89

3.20

.85

HEALTH EVALUATION

3.95

.72

3.86

.80

HEALTH ORIENTATION

3.61

.70

3.75

.70

ILLNESS ORIENTATION

3.18

.83

3.21

.84

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION

3.50

.63

3.23

.74

OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION

2.47

.92

3.03

.96

SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

2.96

.62

3.57

.73

FACTOR SUBSCALES:

ADDITIONAL SUBSCALES:

NOTE: Norms for all except two subscales are derived from the U.S. national survey data (Cash et al., 1985, 1986), based on 996 males and 1070 females. Exceptions are the BASS and SelfClassified Weight, whose items or response format were altered subsequent to the 1985 survey. These two subscales' norms are derived from several combined samples studied by the author with Ns = 804 women and 335 men. Sample participants were 18 years of age or older.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

7

RELIABILITIES OF THE MBSRQ SUBSCALES

MALES FEMALES __________________________ _______________________ CRONBACH'S 1-MONTH CRONBACH'S 1-MONTH ALPHA TEST-RETEST ALPHA TEST-RETEST ___________________________________________________ FACTOR SUBSCALES: APPEARANCE EVALUATION

.88

.81

.88

.91

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

.88

.89

.85

.90

FITNESS EVALUATION

.77

.76

.77

.79

FITNESS ORIENTATION

.91

.73

.90

.94

HEALTH EVALUATION

.80

.71

.83

.79

HEALTH ORIENTATION

.78

.76

.78

.85

ILLNESS ORIENTATION

.78

.79

.75

.78

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION

.77

.86

.73

.74

OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION

.73

.79

.76

.89

SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

.70

.86

.89

.74

ADDITIONAL SUBSCALES:

NOTE: Internal consistencies are based on normative samples (see page 5). Test-retest correlations are derived from college student samples.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

8

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL BODY-SELF RELATIONS QUESTIONNAIRE: PUBLISHED EMPIRICAL STUDIES BY THE AUTHOR The following publications by the author report investigations using the MBSRQ or its specific subscales. Because of numerous requests, reprints are often in short supply. Please request a reprint only if unavailable through your library. Cash, T.F., Ancis, J.R., & Strachan, M.D. (1997). Gender attitudes, feminist identity, and body images among college women. Sex Roles, 36, 433-447. Cash, T.F., & Lavallee, D.M. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral body-image therapy: Further evidence of the efficacy of a self-directed program. Journal of Rational-Emotive and CognitiveBehavior Therapy, 15, 281-294. Huddy, D.C., & Cash, T.F. (1997). Body-image attitudes among male marathon runners: A controlled comparative study. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 28, 227236. Lewis, R.J., Cash, T.F., Jacobi, L., & Bubb-Lewis, C. (1997). Prejudice toward fat people: The development and validation of the Anti-fat Attitudes Test. Obesity Research, 5, 297-307. Muth, J.L., & Cash, T.F. (1997). Body-image attitudes: What difference does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 1438-1452. Cash, T.F., & Labarge, A.S. (1996). Development of the Appearance Schemas Inventory: A new cognitive body-image assessment. CognitiveTherapy & Research, 20, 37-50. Rieves, L., & Cash, T.F. (1996). Reported social developmental factors associated with women’s body-image attitudes. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 11, 63-78. Cash, T.F. (1995). Developmental teasing about physical appearance: Retrospective descriptions and relationships with body image. Personality and Social Behavior: An International Journal, 23, 123-130. Cash, T.F., & Henry, P.E. (1995). Women's body images: The results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Sex Roles, 33, 19-28. Cash, T.F., & Szymanski, M.L. (1995). The development and validation of the Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64, 466-477. Grant, J.R., & Cash, T.F. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral body-image therapy: Comparative efficacy of group and modest-contact treatments. Behavior Therapy, 26, 69-84. Szymanski, M.L., & Cash, T.F. (1995). Body-image disturbances and self-discrepancy theory: Expansion of the Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14, 134-146.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

9

Cash, T.F. (1994). Body image and weight changes in a multisite comprehensive very-low-calorie diet program. Behavior Therapy, 25, 239-254. Cash, T.F. (1994). Body-image attitudes: Evaluation, investment, and affect. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78, 1168-1170. Cash, T.F. (1994). The Situational Inventory of Body-Image Dysphoria: Contextual assessment of a negative body image. the Behavior Therapist, 17, 133-134. Cash, T.F., Novy, P.L., & Grant J.R. (1994). Why do women exercise?: Factor analysis and further validation of the Reasons for Exercise Inventory. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78, 539-544. Jacobi, L., & Cash, T.F. (1994). In pursuit of the perfect appearance: Discrepancies among self- and ideal-percepts of multiple physical attributes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 379-396. Cash, T.F. (1993). Body-image attitudes among obese enrollees in a commercial weight-loss program. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 77, 1099-1103. Cash, T.F., Price, V., & Savin, R. (1993). The psychosocial effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: Comparisons with balding men and female control subjects. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 29, 568-575. Cash, T.F. (1992). Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia among men. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 26, 926-931. Bond, S., & Cash, T.F. (1992). Black beauty: Skin color and body images among African-American college females. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 11, 874-888. Cash, T.F., Grant, J.R., Schovlin, J.M., & Lewis, R.J. (1992). Are inaccuracies in self-reported weight motivated distortions? Perceptual and Motor Skills, 74, 209-210. Cash, T.F., & Jacobi, L. (1992). Looks aren't everything (to everybody): The strength of ideals of physical appearance. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 7, 621-630. Rucker, C.E., & Cash, T.F. (1992). Body images, body-size perceptions, and eating behaviors among African-American and White college women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 12, 291-300. Cash, T.F. (1991). Binge-eating and body images among the obese: A further evaluation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6, 367-376. Cash, T.F., Wood, K.C, Phelps, K.D., & Boyd, K. (1991). New assessments of weight-related body-image derived from extant instruments. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 73, 235-241.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

10

Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & Mikulka, P.J. (1990). Attitudinal body image assessment: Factor analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 135-144. Cash, T.F., Counts, B., & Huffine, C.E. (1990). Current and vestigial effects of overweight among women: Fear of fat, attitudinal body image, and eating behaviors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 12, 157-167. Cash, T.F., & Hicks, K.L. (1990). Being fat versus thinking fat: Relationships with body image, eating behaviors, and well-being. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 327-341. Keeton, W.P., Cash, T.F., & Brown, T.A. (1990). Body image or body images?: Comparative, multidimensional assessment among college students. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, 213-230. Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & Lewis, R.J. (1989). Body-image disturbances in adolescent female binge-purgers: A brief report of the results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30, 605-613. Cash, T.F. (1989). Body-image affect: Gestalt versus summing the parts. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69, 17-18. Cash, T.F., & Brown, T.A. (1989). Gender and body images: Stereotypes and realities. Sex Roles, 21, 361-373. Cash, T.F., Counts, B., Hangen, J., & Huffine, C. (1989). How much do you weigh?: Determinants of validity of self-reported body weight. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69, 248-250. Butters, J.W., & Cash, T.F. (1987). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of women's body-image dissatisfaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 889-897. Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & Noles, S.W. (1986). Perceptions of physical attractiveness among college students: Selected determinants and methodological matters. Journal of Social Psychology, 126, 305-316. Cash, T.F., & Green, G.K. (1986). Body weight and body image among college women: Perception, cognition, and affect. Journal of Personality Assessment, 50, 290-301. Cash, T.F., Winstead, B.W., & Janda, L.H. (1986). The great American shape-up: Body image survey report. Psychology Today, 20(4), 30-37. Cash, T.F., Winstead, B.A., & Janda, L.H. (1985). Your body, yourself: A Psychology Today reader survey. Psychology Today, 19 (7), 22-26. Noles, S.W., Cash, T.F., & Winstead, B.A. (1985). Body image, physical attractiveness, and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 88-94.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

11

BODY IMAGE: CONCEPTUAL/THEORETICAL PUBLICATIONS BY THE AUTHOR Books Cash, T.F. (1997). The body image workbook: An 8-step program for learning to like your looks. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. Cash, T.F. (1995). What do you see when you look in the mirror?: Helping yourself to a positive body image. New York: Bantam Books. Cash, T.F. (1991). Body-image therapy: A program for self-directed change. Audiocassette series with client workbook and clinician's manual. New York: Guilford. Cash, T.F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.) (1990). Body images: Development, deviance, and change. New York: Guilford Press. Chapters and Articles Cash, T.F. (in press). Women’s body images: For better or for worse. In G. Wingood and R. DiClemente (Eds.), Handbook of women’s sexual and reproductive health. New York: Plenum. Cash, T.F. (in press). Body image. In A. Kazdin (Ed.), The encyclopedia of psychology. American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press. Cash, T.F. (1999). The psychosocial consequences of androgenetic alopecia: A review of the research literature. British Journal of Dermatology, 141(3), 398-405. Cash, T.F., & Roy, R.E. (1999). Pounds of flesh: Weight, gender, and body images. In J. Sobal & D. Maurer (Eds.), Interpreting weight: The social management of fatness and thinness (pp. 209-228). Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. Cash, T.F., & Strachan, M.D. (1999). Body images, eating disorders, and beyond. In R. Lemberg (Ed.), Eating disorders: A reference sourcebook (pp. 27-36). Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press. Cash, T.F. (1997). The emergence of negative body images. In E. Blechman & K. Brownell (Eds.), Behavioral medicine for women: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 386-391). New York: Guilford Press. Cash, T.F., & Deagle, E.A. (1997). The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 22, 107-125. Cash, T.F. (1996). Body image and cosmetic surgery: The psychology of physical appearance. American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery, 13, 345-351.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

12

Cash, T.F. (1990). The psychology of physical appearance: Aesthetics, attributes, and images. In Cash, T.F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.), Body images: Development, deviance, and change (pp. 51-79). New York: Guilford Press. Pruzinsky, T., & Cash, T.F. (1990). Integrative themes in body-image development, deviance, and change. In Cash, T.F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.), Body images: Development, deviance, and change (pp. 337-349). New York: Guilford Press. Cash, T.F. (1985). Physical appearance and mental health. In J.A. Graham & A. Kligman (Eds.), Psychology of cosmetic treatments (pp. 196-216). New York: Praeger Scientific.

1

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL BODY-SELF RELATIONS QUESTIONNAIRE THOMAS F. CASH, PH.D Professor of Psychology Old Dominion University Norfolk, VA 23529-0267 Office phone: (757) 683-4439 University E-mail: [email protected] Personal E-mail: [email protected]

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) is a 69-item self-report inventory for the assessment of self-attitudinal aspects of the body-image construct. Body image is conceived as one’s attitudinal dispositions toward the physical self (Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990). As attitudes, these dispositions include evaluative, cognitive, and behavioral components. Moreover, the physical self encompasses not only one’s physical appearance but also the body’s competence or “fitness” and its biological integrity or “health/illness.” An initial version of this instrument in 1983 contained 294 items and was termed the BSRQ. Subsequent versions iteratively eliminated or replaced items on the basis of rational/conceptual and psychometric criteria. In 1985, Cash, Winstead, and Janda used the instrument in a national body-image survey. From over 30,000 respondents, approximately 2,000 were randomly sampled, stratified on the basis of the sex X age distribution in the U.S. population. In addition to the original publication of survey results (see Cash et al., 1986), numerous publications have developed from analysis of this database and from research with other diverse samples (see appended references). A cross-validated principal-components analysis of the original database (Brown, Cash, & Mikulka, 1990) supports the conceptual components of the instrument. The MBSRQ’s Factor Subscales reflect two dispositional dimensions—“Evaluation” and cognitive-behavioral “Orientation” –vis-à-vis each of the three somatic domains of “Appearance,” Fitness,” and “Health/Illness.” A minor exception was an emergence of separate Health and Illness Orientation factors. In addition to its seven Factor Subscales, the MBSRQ has three special multiitem subscales: (1) The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS) approaches body-image evaluation as dissatisfaction-satisfaction with body areas and attributes (similar to earlier inventories, such as Secord and Jourard’s Body Cathexis Scale, Bohrnstedt’s Body Parts Satisfaction Scale, and Franzoi’s Body Esteem Scale). (2) The Overweight Preoccupation Scale assesses fat anxiety, weight vigilance, dieting, and eating restraint. (3) The Self-Classified Weight Scale assesses self-appraisals of weight from “very underweight” to “very overweight.” The MBSRQ is intended for use with adults and adolescents (15 years or older). The instrument is not appropriate for children. If researchers administer the full 69-item

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

2

MBSRQ but wish to reduce the number of derived scores, the Fitness Evaluation and Health Evaluation scales may be combined (i.e., averaged) to calculate a Fitness/Health Evaluation measure. Similarly, an average of the Fitness Orientation and Health Orientation scores may be computed to construct a Fitness/Health Orientation measure. Many body-image researchers are principally interested in the appearance-related subscales of the MBSRQ and wish to administer a shorter questionnaire that excludes the fitness and health items. Accordingly, they may elect to use the 34-item MBSRQAS (MBSRQ-Appearance Scales) version of the instrument. The MBSRQ-AS includes the following subscales: Appearance Evaluation, Appearance Orientation, Overweight Preoccupation, Self-Classified Weight, and the BASS. Unique in its multidimensional assessment, the MBSRQ has been used extensively and successfully in body-image research. Investigations range from basic psychometric studies to applied and clinical research, involving both correlational and experimental methodologies. The MBSRQ has been employed in national survey research, studies of “normal” college students, investigations of obesity, eating disturbance, androgenetic alopecia, facial acne, and physical exercise, and outcome studies of body-image therapy. The MBSRQ manual provides interpretive information about its subscales (PAGE 3), scoring formulae (PAGES 4-5), gender-specific norms (PAGE 6), and reliability data (PAGE 7). All subscales possess acceptable internal consistency and stability. References are also given for the author’s published research pertinent to the validity and clinical utility of the MBSRQ (PAGES 8-10). These cited sources confirm the MBSRQ’s strong convergent, discriminant, and construct validities. Terms and Conditions of Use of the MBSRQ The MBSRQ and its manual are available for a nominal fee from Dr. Cash’s web site. By providing certain identifying information and agreeing to honor payment of the fee to him, requestors can print (but not download) one copy of the MBSRQ and MBSRQ-AS, as well as the manual. Requestors are permitted limited duplication of the materials for research or clinical purposes. Conditions of use are as follows: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Period of use cannot exceed two years. Duplicated copies exceeding 500 require the author’s written permission. Distribution for use by others is prohibited. Re-typing or modification of the MBSRQ items is prohibited. Any commercial use of the materials, other than use in research or clinical practice, is prohibited. (6) Any document (i.e., technical report, thesis, dissertation, or published article) resulting from use of the MBSRQ will include its proper citation.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

3

THE MBSRQ SUBSCALES: INTERPRETATIONS The Factor Subscales: APPEARANCE EVALUATION: Feelings of physical attractiveness or unattractiveness; satisfaction or dissatisfaction with one's looks. High scorers feel mostly positive and satisfied with their appearance; low scorers have a general unhappiness with their physical appearance. APPEARANCE ORIENTATION: Extent of investment in one's appearance. High scorers place more importance on how they look, pay attention to their appearance, and engage in extensive grooming behaviors. Low scorers are apathetic about their appearance; their looks are not especially important and they do not expend much effort to 'look good'. FITNESS EVALUATION: Feelings of being physically fit or unfit. High scorers regard themselves as physically fit, 'in shape', or athletically active and competent. Low scorers feel physically unfit, 'out of shape', or athletically unskilled. High scorers value fitness and are actively involved in activities to enhance or maintain their fitness. Low scorers do not value physical fitness and do not regularly incorporate exercise activities into their lifestyle. FITNESS ORIENTATION: Extent of investment in being physically fit or athletically competent. High scorers value fitness and are actively involved in activities to enhance or maintain their fitness. Low scorers do not value physical fitness and do not regularly incorporate exercise activities into their lifestyle. HEALTH EVALUATION: Feelings of physical health and/or the freedom from physical illness. High scorers feel their bodies are in good health. Low scorers feel unhealthy and experience bodily symptoms of illness or vulnerability to illness. HEALTH ORIENTATION: Extent of investment in a physically healthy lifestyle. High scorers are 'health conscious' and try to lead a healthy lifestyle. Low scorers are more apathetic about their health. ILLNESS ORIENTATION: Extent of reactivity to being or becoming ill. High scorers are alert to personal symptoms of physical illness and are apt to seek medical attention. Low scorers are not especially alert or reactive the physical symptoms of illness. Additional MBSRQ Subscales: BODY AREAS SATISFACTION SCALE: Similar to the Appearance Evaluation subscale, except that the BASS taps satisfaction with discrete aspects of one's appearance. High composite scorers are generally content with most areas of their body. Low scorers are unhappy with the size or appearance of several areas. OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION: This scale assesses a construct reflecting fat anxiety, weight vigilance, dieting, and eating restraint. SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT: This scale reflects how one perceives and labels one's weight, from very underweight to very overweight.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

4

ITEM NUMERS FOR EACH MBSRQ SUBSCALE (*REVERSE-SCORED ITEMS) APPEARANCE EVALUATION

5

11

21

30

39

42*

48*

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

1

2

12

13

22

23*

31

32*

40*

41

49*

50

FITNESS EVALUATION

24

33*

51

FITNESS ORIENTATION

3

4

6*

14

15*

16*

25*

26

34*

35

43*

44

53

HEALTH EVALUATION

7

17*

27

36*

45*

54

HEALTH ORIENTATION

8

9

18

19

28*

29

38*

52

ILLNESS ORIENTATION

37*

46

47*

55

56

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION

10

20

57

58

SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

59

60

MBSRQ subscale scores are the means of the constituent items after reversing contraindicative items (i.e., 1 = 5, 2 = 4, 4 = 2, 5 = 1). Alternatively, the formulae below may be used, which reverse-score items by subtracting them and adding a constant (i.e., any reversed item is scored as 6 minus the response value). Items are denoted as B1 to B69. COMPUTE APPEVAL = (B5+B11+B21+B30+B39-B42-B48+12)/7. COMPUTE APPOR = (B1+B2+B12+B13+B22+B31+B41+B50-B23-B32-B40-B49+24)/12. COMPUTE FITEVAL = (B24+B51-B33+6)/3. COMPUTE FITOR = (B3+B4 +B14+B26+B35+B44+B53-B6-B15-B16-B25-B34-B43+36)/13. COMPUTE HLTHEVAL = (B7+B27+B54-B17-B36-B45+18)/6. COMPUTE HLTHOR = (B8+B9+B18+B19+B29+B52-B28-B38+12)/8. COMPUTE ILLOR = (B46+B55+B56-B37-B47+12)/5. COMPUTE BASS = (B61+B62+B63+B64+B65+B66+B67+B68+B69)/9. COMPUTE OWPREOC = (B10+B20+B57+B58)/4. COMPUTE WTCLASS = (B59+B60)/2.

69

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

5

ITEM NUMERS FOR SUBSCALES OF THE MBSRQ-AS (*REVERSE-SCORED ITEMS) APPEARANCE EVALUATION

3

5

9

12

15

18*

19*

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

1

2

6

7

10

11*

13

14*

16*

17

20*

21

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

4

8

22

23

24

25

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

33

MBSRQ-AS subscale scores are the means of the constituent items after reversing contra-indicative items (i.e., 1 = 5, 2 = 4, 4 = 2, 5 = 1). Alternatively, the formulae below may be used, which reverse-score items by subtracting them and adding a constant (i.e., any reversed item is scored as 6 minus the response value). Items are denoted as B1 to B34. COMPUTE APPEVAL = (B3+B5+B9+B12+B15-B18-B19+12)/7. COMPUTE APPOR = (B1+B2+B6+B7+B10+B13+B17+B21-B11-B14-B16-B20+24)/12. COMPUTE BASS = (B26+B27+B28+B29+B30+B31+B32+B33+B34)/9. COMPUTE OWPREOC = (B4+B8+B22+B23)/4. COMPUTE WTCLASS = (B24+B25)/2.

34

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

6

ADULT NORMS FOR THE MBSRQ SUBSCALES

MALES

FEMALES

MBSRQ SUBSCALES MEAN SD

MEAN SD

APPEARANCE EVALUATION

3.49

.83

3.36

.87

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

3.60

.68

3.91

.60

FITNESS EVALUATION

3.72

.91

3.48

.97

FITNESS ORIENTATION

3.41

.89

3.20

.85

HEALTH EVALUATION

3.95

.72

3.86

.80

HEALTH ORIENTATION

3.61

.70

3.75

.70

ILLNESS ORIENTATION

3.18

.83

3.21

.84

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION

3.50

.63

3.23

.74

OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION

2.47

.92

3.03

.96

SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

2.96

.62

3.57

.73

FACTOR SUBSCALES:

ADDITIONAL SUBSCALES:

NOTE: Norms for all except two subscales are derived from the U.S. national survey data (Cash et al., 1985, 1986), based on 996 males and 1070 females. Exceptions are the BASS and SelfClassified Weight, whose items or response format were altered subsequent to the 1985 survey. These two subscales' norms are derived from several combined samples studied by the author with Ns = 804 women and 335 men. Sample participants were 18 years of age or older.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

7

RELIABILITIES OF THE MBSRQ SUBSCALES

MALES FEMALES __________________________ _______________________ CRONBACH'S 1-MONTH CRONBACH'S 1-MONTH ALPHA TEST-RETEST ALPHA TEST-RETEST ___________________________________________________ FACTOR SUBSCALES: APPEARANCE EVALUATION

.88

.81

.88

.91

APPEARANCE ORIENTATION

.88

.89

.85

.90

FITNESS EVALUATION

.77

.76

.77

.79

FITNESS ORIENTATION

.91

.73

.90

.94

HEALTH EVALUATION

.80

.71

.83

.79

HEALTH ORIENTATION

.78

.76

.78

.85

ILLNESS ORIENTATION

.78

.79

.75

.78

BODY AREAS SATISFACTION

.77

.86

.73

.74

OVERWEIGHT PREOCCUPATION

.73

.79

.76

.89

SELF-CLASSIFIED WEIGHT

.70

.86

.89

.74

ADDITIONAL SUBSCALES:

NOTE: Internal consistencies are based on normative samples (see page 5). Test-retest correlations are derived from college student samples.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

8

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL BODY-SELF RELATIONS QUESTIONNAIRE: PUBLISHED EMPIRICAL STUDIES BY THE AUTHOR The following publications by the author report investigations using the MBSRQ or its specific subscales. Because of numerous requests, reprints are often in short supply. Please request a reprint only if unavailable through your library. Cash, T.F., Ancis, J.R., & Strachan, M.D. (1997). Gender attitudes, feminist identity, and body images among college women. Sex Roles, 36, 433-447. Cash, T.F., & Lavallee, D.M. (1997). Cognitive-behavioral body-image therapy: Further evidence of the efficacy of a self-directed program. Journal of Rational-Emotive and CognitiveBehavior Therapy, 15, 281-294. Huddy, D.C., & Cash, T.F. (1997). Body-image attitudes among male marathon runners: A controlled comparative study. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 28, 227236. Lewis, R.J., Cash, T.F., Jacobi, L., & Bubb-Lewis, C. (1997). Prejudice toward fat people: The development and validation of the Anti-fat Attitudes Test. Obesity Research, 5, 297-307. Muth, J.L., & Cash, T.F. (1997). Body-image attitudes: What difference does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 1438-1452. Cash, T.F., & Labarge, A.S. (1996). Development of the Appearance Schemas Inventory: A new cognitive body-image assessment. CognitiveTherapy & Research, 20, 37-50. Rieves, L., & Cash, T.F. (1996). Reported social developmental factors associated with women’s body-image attitudes. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 11, 63-78. Cash, T.F. (1995). Developmental teasing about physical appearance: Retrospective descriptions and relationships with body image. Personality and Social Behavior: An International Journal, 23, 123-130. Cash, T.F., & Henry, P.E. (1995). Women's body images: The results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Sex Roles, 33, 19-28. Cash, T.F., & Szymanski, M.L. (1995). The development and validation of the Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64, 466-477. Grant, J.R., & Cash, T.F. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral body-image therapy: Comparative efficacy of group and modest-contact treatments. Behavior Therapy, 26, 69-84. Szymanski, M.L., & Cash, T.F. (1995). Body-image disturbances and self-discrepancy theory: Expansion of the Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14, 134-146.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

9

Cash, T.F. (1994). Body image and weight changes in a multisite comprehensive very-low-calorie diet program. Behavior Therapy, 25, 239-254. Cash, T.F. (1994). Body-image attitudes: Evaluation, investment, and affect. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78, 1168-1170. Cash, T.F. (1994). The Situational Inventory of Body-Image Dysphoria: Contextual assessment of a negative body image. the Behavior Therapist, 17, 133-134. Cash, T.F., Novy, P.L., & Grant J.R. (1994). Why do women exercise?: Factor analysis and further validation of the Reasons for Exercise Inventory. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78, 539-544. Jacobi, L., & Cash, T.F. (1994). In pursuit of the perfect appearance: Discrepancies among self- and ideal-percepts of multiple physical attributes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 379-396. Cash, T.F. (1993). Body-image attitudes among obese enrollees in a commercial weight-loss program. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 77, 1099-1103. Cash, T.F., Price, V., & Savin, R. (1993). The psychosocial effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: Comparisons with balding men and female control subjects. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 29, 568-575. Cash, T.F. (1992). Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia among men. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 26, 926-931. Bond, S., & Cash, T.F. (1992). Black beauty: Skin color and body images among African-American college females. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 11, 874-888. Cash, T.F., Grant, J.R., Schovlin, J.M., & Lewis, R.J. (1992). Are inaccuracies in self-reported weight motivated distortions? Perceptual and Motor Skills, 74, 209-210. Cash, T.F., & Jacobi, L. (1992). Looks aren't everything (to everybody): The strength of ideals of physical appearance. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 7, 621-630. Rucker, C.E., & Cash, T.F. (1992). Body images, body-size perceptions, and eating behaviors among African-American and White college women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 12, 291-300. Cash, T.F. (1991). Binge-eating and body images among the obese: A further evaluation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6, 367-376. Cash, T.F., Wood, K.C, Phelps, K.D., & Boyd, K. (1991). New assessments of weight-related body-image derived from extant instruments. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 73, 235-241.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

10

Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & Mikulka, P.J. (1990). Attitudinal body image assessment: Factor analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 135-144. Cash, T.F., Counts, B., & Huffine, C.E. (1990). Current and vestigial effects of overweight among women: Fear of fat, attitudinal body image, and eating behaviors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 12, 157-167. Cash, T.F., & Hicks, K.L. (1990). Being fat versus thinking fat: Relationships with body image, eating behaviors, and well-being. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 327-341. Keeton, W.P., Cash, T.F., & Brown, T.A. (1990). Body image or body images?: Comparative, multidimensional assessment among college students. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, 213-230. Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & Lewis, R.J. (1989). Body-image disturbances in adolescent female binge-purgers: A brief report of the results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30, 605-613. Cash, T.F. (1989). Body-image affect: Gestalt versus summing the parts. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69, 17-18. Cash, T.F., & Brown, T.A. (1989). Gender and body images: Stereotypes and realities. Sex Roles, 21, 361-373. Cash, T.F., Counts, B., Hangen, J., & Huffine, C. (1989). How much do you weigh?: Determinants of validity of self-reported body weight. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69, 248-250. Butters, J.W., & Cash, T.F. (1987). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of women's body-image dissatisfaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 889-897. Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & Noles, S.W. (1986). Perceptions of physical attractiveness among college students: Selected determinants and methodological matters. Journal of Social Psychology, 126, 305-316. Cash, T.F., & Green, G.K. (1986). Body weight and body image among college women: Perception, cognition, and affect. Journal of Personality Assessment, 50, 290-301. Cash, T.F., Winstead, B.W., & Janda, L.H. (1986). The great American shape-up: Body image survey report. Psychology Today, 20(4), 30-37. Cash, T.F., Winstead, B.A., & Janda, L.H. (1985). Your body, yourself: A Psychology Today reader survey. Psychology Today, 19 (7), 22-26. Noles, S.W., Cash, T.F., & Winstead, B.A. (1985). Body image, physical attractiveness, and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 88-94.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

11

BODY IMAGE: CONCEPTUAL/THEORETICAL PUBLICATIONS BY THE AUTHOR Books Cash, T.F. (1997). The body image workbook: An 8-step program for learning to like your looks. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. Cash, T.F. (1995). What do you see when you look in the mirror?: Helping yourself to a positive body image. New York: Bantam Books. Cash, T.F. (1991). Body-image therapy: A program for self-directed change. Audiocassette series with client workbook and clinician's manual. New York: Guilford. Cash, T.F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.) (1990). Body images: Development, deviance, and change. New York: Guilford Press. Chapters and Articles Cash, T.F. (in press). Women’s body images: For better or for worse. In G. Wingood and R. DiClemente (Eds.), Handbook of women’s sexual and reproductive health. New York: Plenum. Cash, T.F. (in press). Body image. In A. Kazdin (Ed.), The encyclopedia of psychology. American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press. Cash, T.F. (1999). The psychosocial consequences of androgenetic alopecia: A review of the research literature. British Journal of Dermatology, 141(3), 398-405. Cash, T.F., & Roy, R.E. (1999). Pounds of flesh: Weight, gender, and body images. In J. Sobal & D. Maurer (Eds.), Interpreting weight: The social management of fatness and thinness (pp. 209-228). Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. Cash, T.F., & Strachan, M.D. (1999). Body images, eating disorders, and beyond. In R. Lemberg (Ed.), Eating disorders: A reference sourcebook (pp. 27-36). Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press. Cash, T.F. (1997). The emergence of negative body images. In E. Blechman & K. Brownell (Eds.), Behavioral medicine for women: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 386-391). New York: Guilford Press. Cash, T.F., & Deagle, E.A. (1997). The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 22, 107-125. Cash, T.F. (1996). Body image and cosmetic surgery: The psychology of physical appearance. American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery, 13, 345-351.

MBSRQ USERS’ MANUAL (Third Revision, January, 2000 )

12

Cash, T.F. (1990). The psychology of physical appearance: Aesthetics, attributes, and images. In Cash, T.F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.), Body images: Development, deviance, and change (pp. 51-79). New York: Guilford Press. Pruzinsky, T., & Cash, T.F. (1990). Integrative themes in body-image development, deviance, and change. In Cash, T.F., & Pruzinsky, T. (Eds.), Body images: Development, deviance, and change (pp. 337-349). New York: Guilford Press. Cash, T.F. (1985). Physical appearance and mental health. In J.A. Graham & A. Kligman (Eds.), Psychology of cosmetic treatments (pp. 196-216). New York: Praeger Scientific.